Author’s note

A life’s worth of decades on Earth, or simply the time of disillusionment?

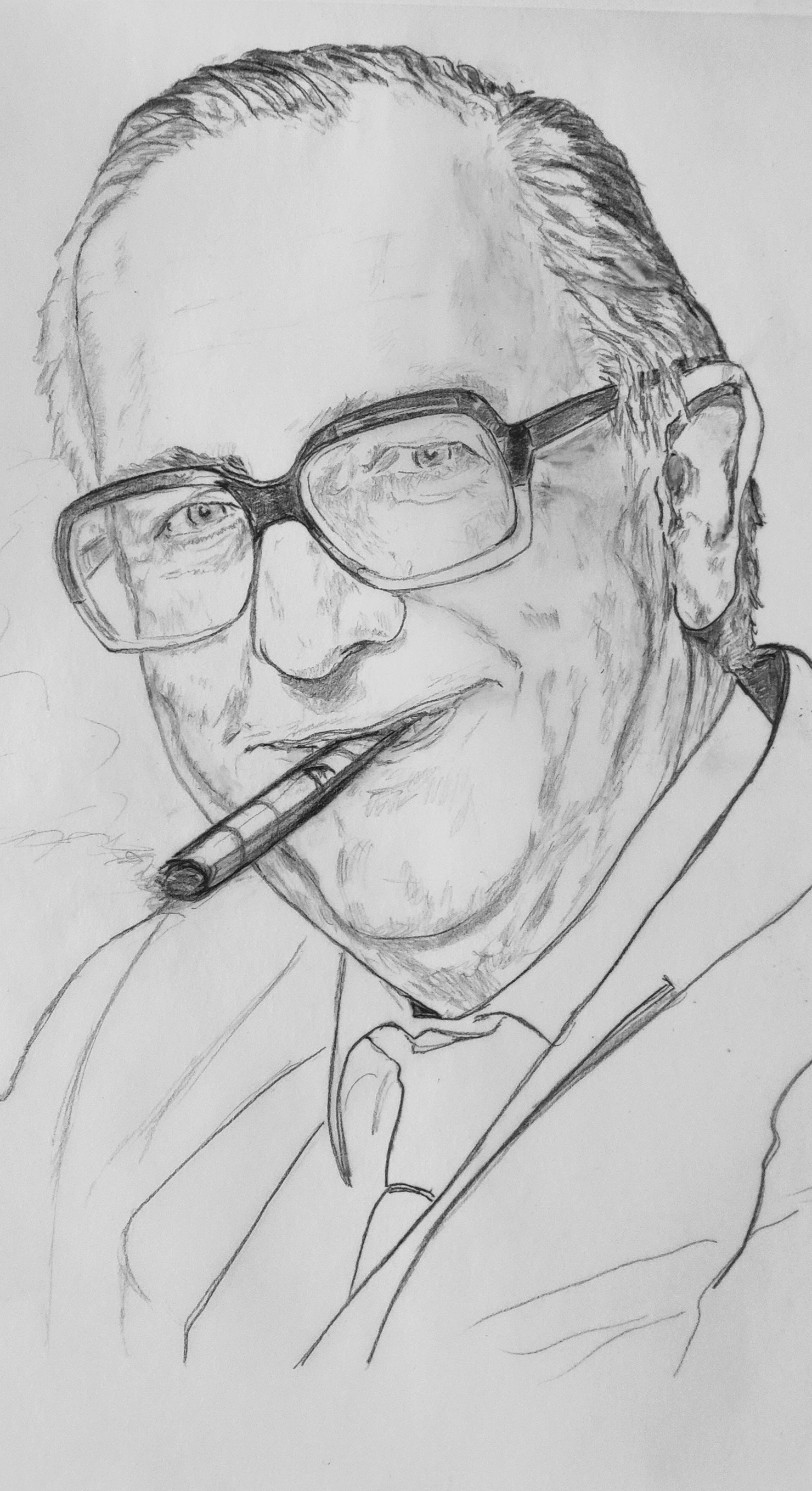

Right at the centre of his own gravity, Tom Sharpe shifts from teacher to writer. Forty-two years of slow maturation (that odd little number again…).

A strong drink against apartheid, which earns him prison and then expulsion back to his homeland. From the dark South African years to the misty Midlands of 1970s England, he keeps firing satirical volleys. The brazenness of the mediocre fascinates him. The alienation of the individual drives him furious.

Sharpe shoots in all directions: codes and etiquette that tape you down exactly where you never wanted to be. The half-century that separates us from the first volume of the Wilt series is one of those that bring us closer. Sideburns and flared trousers may have fallen away; oppressions, on the other hand, cling on. Nothing really changes.

So don’t trust the face or the vague “has-been” impression. This is a writer who feels contemporary in every age. Even in those still to come.

Beaumarchais hurried to laugh at everything, for fear of being obliged to weep. Tom Sharpe chose the same pair of glasses. Put them on as well: they help you see more clearly. Better still, they help you find a way through.

A pity my ophthalmologist doesn’t prescribe that model… — TNoC